Laury A. Echavarria

As the world grapples with the urgent challenges posed by the climate crisis, the debate over the efficacy of democratic politics in addressing this global issue has gained prominence. Over the past decades, as nations confront environmental challenges such as carbon emissions and the climate crisis, democratic political frameworks have played a central role.

In the ongoing discourse surrounding the climate crisis, optimists argue that democratic politics offer the most promising avenue for addressing this global challenge. Advocates of this viewpoint contend that democratic systems, with their emphasis on citizen participation, transparency, and accountability, are better equipped to implement effective climate policies. However, a critical evaluation of this position reveals both strengths and weaknesses, which must be carefully considered to assess its validity.

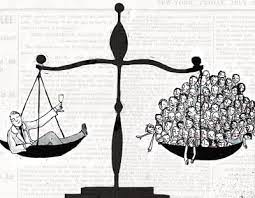

Democratic politics have struggled to effectively address the climate crisis due to inequalities of influence among states at the global level. Certain powerful nations wield disproportionate power in decision-making structures like the UN Security Council, dominated by Western powers. Consequently, smaller states lack the ability to protect themselves from climate impacts and heavily rely on more powerful states to act. This lack of representation for populous nations and regions aggravate the problem. Additionally, global climate agreements proposed in democratic politics have struggled to deliver significant carbon emissions reductions due to their voluntary nature and lack of enforceability. Despite efforts to strengthen climate action through agreements like COP 21 (Paris) and COP 26 (Glasgow), global carbon emissions continue to rise, indicating a failure of democratic politics to effectively address the urgency of the climate crisis. (Tollefson, 2021).

In assessing the optimist’s view favouring democratic politics as the solution to the climate crisis, we must heed the perspectives of notable proponents. Graham Smith, a Politics Professor at the Centre for the Study of Democracy, explored whether democracy can effectively address climate challenges. He holds an optimistic stance rooted in democracy’s adaptability and potential, despite recognizing hurdles like democratic myopia. Smith believes in democracy’s capacity to evolve and address global issues like climate change, stressing the need for diversity and creativity in governance structures.

Smith also emphasizes the importance of experimenting with different forms of democracy beyond traditional electoral politics. This experimentation fosters creativity and imagination, offering hope for finding innovative democratic responses to the climate crisis.

Benjamin R. Barber, a US political theorist, suggests empowering cities to address climate change, aligning with the optimist’s belief in democratic systems as the best solution. By promoting local democratic politics and urban sovereignty, Barber aims to overcome the limitations of global agreements and national politics in tackling climate issues, adopting the term Glocality,. He advocates for cities to lead climate efforts, showcasing successful local initiatives and promoting citizen action. This perspective reinforces the optimist’s view that grassroots democratic politics offer promise in addressing climate challenges. (Barber, B.R. (2017)

Reggio Emilia, an Italian city, exemplifies Barber and Smith’s point by embracing diversity, creativity, and experimentation within democratic governance structures. The city prioritises social welfare policies and fosters a culture of cooperation and solidarity among citizens. Reggio Emilia has committed to inclusivity and values the contributions of individuals, businesses, and civil society organizations in achieving the goals of Agenda 2030, recognizing it as a collective effort beyond the city government’s sole responsibility. (UN (no date – c) Sustainable development goals)

Alongside these efforts, there has been a concerning trend towards authoritarianism, with statistics indicating a steady rise over the last 16 years. This authoritarian surge raises questions about democracy’s capacity to safeguard the future, particularly in addressing existential threats like the climate crisis. Some advocates of democracy acknowledge concerns about its current weaknesses, divisions, and ineffectiveness in making crucial decisions to prevent catastrophe. There are even suggestions for a more authoritarian approach based on expert knowledge. Scientist James Lovelock, known for his Gaia theory, feared that the severity of the climate crisis would require significant changes in decision-making:

‘You’ve got to have a few people with authority who you trust who are running it … But it can’t happen in a modern democracy … even the best democracies agree that when a major war approaches, democracy must be put on hold for the time being. I have a feeling that climate change may be an issue as severe as a war. It may be necessary to put democracy on hold for a while’. (Lovelock, 2010)

Data from The World Values Survey reveals concerning shifts in public attitudes towards democracy, with significant support for strong leaders and expert rule over democratic processes: In the United States, 37% support bypassing parliament and elections for a strong leader, while in Indonesia, it’s 59%. Similarly, in the UK and Nigeria, 60% and 65% respectively favour experts making decisions over the government. Additionally, there’s a decline in young people’s faith in democracy, with only 31% in the US born in the 1980s considering it essential compared to 72% born before WWII. This highlights the urgent need for reevaluating democratic governance structures. (World Values Survey, 2020c)

Additionally, sources such as The Economist and Freedom House reveal a worrying trend of diminishing democratic governance globally. Full democracies represent a minority of countries and populations, with flawed democracies and authoritarian regimes prevailing.These trends clearly underscore the challenges facing democratic governance in confronting global crises. (The Economist, 2022)

However, these setbacks also highlight the need for continued individual efforts to evolve and strengthen democratic governance, promoting inclusivity in decision-making processes. Initiatives such as ‘geocality’ proposed by Barber showcase how democratic systems can adapt to effectively tackle climate issues at the local level. By empowering communities and fostering citizen engagement, democratic politics offer a pathway towards developing robust and legitimate climate policies that garner broad public support.

We must recognize that Democratic politics can be vulnerable to political polarisation, especially on contentious issues like climate change. Divisive rhetoric and ideological differences may hinder consensus-building and delay decisive action, worsening the climate crisis. Nevertheless, democratic values such as citizen participation stand out as a more convincing perspective providing a viable foundation for confronting these complex global issues. The advocacy for innovative democratic practices, such as citizens’ assemblies and local empowerment, exemplifies the adaptability and potential of democratic governance structures.

While there may be shortcomings, the optimistic view of democratic politics provides a more persuasive governmental approach for addressing the urgency of the climate crisis. By harnessing the collective wisdom and ingenuity of citizens, democratic governance can navigate complex challenges and pave the way for a sustainable future. Therefore, despite the challenges and criticisms, democratic politics remain a vital and promising avenue for tackling the climate crisis and ensuring a better world for future generations.

Perhaps there may be a misguided perception here: When we assert that democratic politics offer the best hope for addressing the climate crisis, we may be framing a political culture that ultimately wouldn’t effectively resolve the crisis. We should reframe it: democratic politics provide the platform from which we can work to rectify our missteps. The geocality concept strongly resonates with this idea. As we increasingly recognize the urgency of the climate crisis, we, in cities, represent a unified force confronting this issue. The proposition that each of us takes this crucial matter into our own hands is the most compelling aspect of this stance. We should utilise democratic liberty to reflect and collectively decide to rectify our past errors, as evidence suggests our current approaches are inadequate in mitigating climate change. Together, we must unite to take action; ultimately, democracy is about the unified voice of each individual working together to address the climate crisis.

References:

O’Cain, A. (2023) ‘Addressing global challenges’, in S. Newcombe, A. O’Cain and M. Pryke (eds) Global challenges: social science in action 3. Milton Keynes: The Open University, pp. 159–191

Smith, D. (2023) ‘Political citizens’, in S. Newcombe, A. O’Cain and M. Pryke (eds) Global challenges: social science in action 3. Milton Keynes: The Open University, pp. 129–158.

Tollefson, J. (2021) ‘COVID curbed carbon emissions in 2020 – but not by much’, Nature, 589(7842), p. 343. Available at: https://www.nature.com/ articles/d41586-021-00090-3

UN (no date – c) Sustainable development goals: the 17 goals. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals

Barber, B.R. (2017) Cool cities: urban sovereignty and the fix for global warming. New Haven, CT; London: Yale University Press.

Lovelock, J. (2010) ‘James Lovelock on the value of sceptics and why Copenhagen was doomed’. Interview with James Lovelock. Interviewed by L. Hickman for the Guardian, 29 March. Available at: https://www.theguardian. com/environment/blog/2010/mar/29/james-lovelock

World Values Survey (2020a,2020b, 2020c) What we do, Who we are, Online data analysis. Available at: https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSContents.jsp

The Economist (2022) A new low for global democracy. Available at: https://www. economist.com/graphic-detail/2022/02/09/a-new-low-for-global-democracy

Freedom House (2023) About us. Available at: https://freedomhouse.org/ about-us

Re “Full democracies represent a minority of countries and populations”

Any alleged expert or layperson who talks about “democracies” AS IF a real democracy ACTUALLY EXISTS ANYWHERE IN THE WORLD (or has existed at any time in ‘human civilization’) is evidently either a fool who’s repeating mindlessly and blindly the propaganda fed to them since they were a kid and/or is a member of the corrupt establishment minions whose job is to disseminate this total lie because any “democracy” of ‘human civilization’ has always been a covert structure of the rule of a few over the many operating behind the pretense name and facade of a “democracy”: https://www.rolf-hefti.com/covid-19-coronavirus.html

“There is no America. There is no democracy. There is only IBM and ITT and AT&T and DuPont, Dow, Union Carbide, and Exxon. Those are the nations of the world today. […]. We no longer live in a world of nations and ideologies […]. The world is a college of corporations, inexorably determined by the immutable laws of business. The world is a business […].” — from the 1976 movie “Network”

“We can either have democracy in this country or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.” — Louis Brandeis, Supreme Court Justice

Does anyone still not see how the deadly game on the foolish public is played … or still does not WANT to see it?

In terms of “experts” or “awake” folks who sell you the fake program of democracies…

“All experts serve the state and the media and only in that way do they achieve their status. Every expert follows his master, for all former possibilities for independence have been gradually reduced to nil by present society’s mode of organization. The most useful expert, of course, is the one who can lie. With their different motives, those who need experts are falsifiers and fools. Whenever individuals lose the capacity to see things for themselves, the expert is there to offer an absolute reassurance.” —Guy Debord

Isn’t it about time for anyone to wake up to the ULTIMATE DEPTH of the human rabbit hole — rather than remain blissfully willfully ignorant in a narcissistic fantasy land and play victim like a little child?

“We’ll know our Disinformation Program is complete when everything the American public [and global public] believes is false.” —William Casey, a former CIA director=a leading psychopathic criminal of the genocidal US regime

“Separate what you know from what you THINK you know.” — Unknown

If you have been injected with Covid jabs/bioweapons and are concerned, then verify what batch number you were injected with at https://howbadismybatch.com

Hi Maar,

I wanted to express my gratitude for your insightful comment on my recent blog post. Your thoughtful perspectives have inspired me to dig deeper into the topic, and I’ve dedicated a new blog post specifically to address the points you raised.

You can find my response in my latest blog post titled “Navigating Complex Perspectives: Responding to Thoughtful Commentary” I’ve made sure to incorporate your ideas and offer further reflections on the matter. I truly appreciate your engagement with my content and look forward to continuing the conversation.

Thank you once again for sharing your thoughts, and I hope you find my response meaningful.

Best regards,

Lae