Data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) website highlights mixed progress toward achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), exposing notable disparities across the 17 objectives. While certain areas have advanced, deep-seated inequalities persist, particularly in income distribution, gender representation, and access to education and healthcare. These disparities intersect across various dimensions, with global discrimination significantly impacting women, people with disabilities, and migrants. Despite efforts over the last 30 years, lower- and middle-income countries have managed to narrow the income gap with wealthier nations by 37%. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has reversed much of this progress, exacerbating existing inequalities and leading to record numbers of refugees, estimated at 34.6 million people, and approximately 7,000 migrant deaths. This paints a concerning picture, with millions projected to remain in extreme poverty and hunger by 2030.

The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) (2023) has identified various aspects of rising poverty and inequalities in Africa. In its report, it emphasizes the role of unequal access to resources like land, capital, and technology, alongside systemic barriers such as weak governance and corruption, in driving these escalating inequalities. This underscores a broader vulnerability in achieving the SDGs, indicating the need for more resilient frameworks to ensure equitable and sustainable development.

Biermann, F. (2022), a professor at Utrecht University, points out that the SDGs are widely discussed in political and corporate spheres, but their impact in terms of concrete actions remains minimal. This gap between rhetoric and reality raises concerns about complacency and greenwashing, where organizations use the SDGs as a superficial badge of sustainability without committing to substantive change. For instance, the World Bank reported a 4.4% increase in inequality among countries between 2019 and 2020, highlighting the disconnect between discourse and tangible progress toward addressing global inequalities.

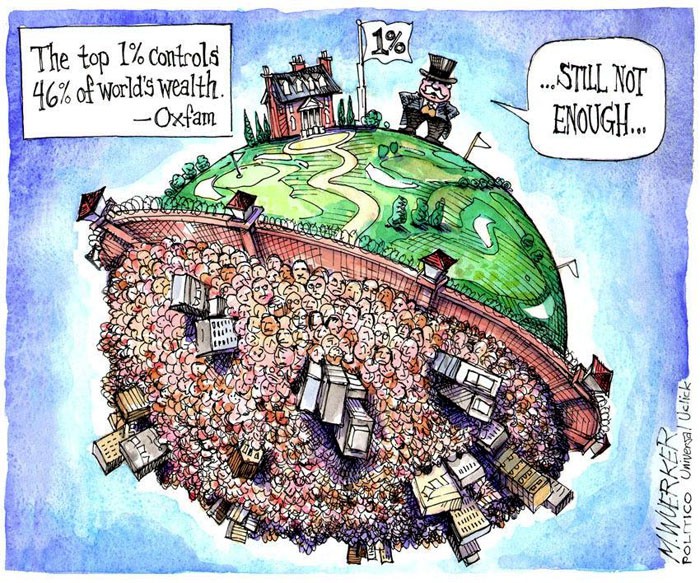

French economist Thomas Piketty (2014) identifies unequal ownership of capital as a major driver of economic inequality. Wealthy individuals control significant capital—real estate, businesses, stocks, and intellectual property—enabling them to generate income without active labor, perpetuating wealth disparities and leading to economic stratification.

Supporters of economic inequality often argue that it incentivises greater productivity. However, this perspective is hard to justify when the wealth gap is so wide; in 2018, for example, the 42 richest individuals owned as much wealth as the poorest half of the world’s population (Oxfam, 2018).

To understand these disparities, Ashe, T., and Clarence, E. (2023) explore the limitations of liberalism in economic decision-making, suggesting that the focus on rational, self-interested individuals often ignores factors like inertia. Behavioral economics provides insights into these non-rational aspects, revealing that people tend to stick with familiar behaviors even when they’re not optimal.

The concepts of ‘core’ and ‘periphery’ further elucidate global inequalities. While core areas, typically urban centres, benefit most from large infrastructure projects, periphery areas, more remote and marginalized, receive fewer benefits and incur higher costs. This division reinforces the pattern of inequality.

Thomas Pogge, a philosopher and ethicist, argues that global poverty and inequality are perpetuated by systemic injustices within international institutions and trade systems. These frameworks tend to favour wealthier nations, creating a cycle of poverty in less developed regions.

Peter Singer, another ethicist, asserts that affluent societies have a moral obligation to help those in need, advocating for more resource redistribution and effective aid programs. His stance complements Pogge’s focus on systemic change, emphasising that ethical considerations should drive efforts to address global inequality and poverty.

References:

OECD (2022), The Short and Winding Road to 2030: Measuring Distance to the SDG Targets, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/af4b630d-en.

Osggod, B. (2023) ‘UN Sustainable Development Goals in spotlight at General Assembly’ , Al Jazeera, 18 September.

United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) (2023) ‘Rising poverty, inequalities threaten Sustainable Development Goals’, African Business, (23 March).

Biermann, F. (2022) ‘UN Sustainable Development Goals failing to have meaningful impact, our research warns’, The Conversation, June 20

Chukwuma, J., Dauncey, E. and Shipman, A. (2023) ‘Economic inequality’, in K. Median, A. O’Cain and M. Pryke (eds) Global challenges: social science in action 2. Milton Keynes: The Open University, pp. 133–169.

Ashe, T. and Clarence, E. (2023) ‘Engaging with global challenges’, in K. Median, A. O’Cain and M. Pryke (eds) Global challenges: social science in action 2. Milton Keynes: The Open University, pp. 103–131.

Cavedon-Taylor, D. (2023) ‘Global justice’, in K. Median, A. O’Cain and M. Pryke (eds) Global challenges: social science in action 2. Milton Keynes: The Open University, pp. 171–197.

Mason, P. (2014) ‘Thomas Piketty’s Capital: everything you need to know about the surprise bestseller’, The Guardian, 28 April.